|

| |

|

|

Crossing the divide

|

Southeast Asia GLOBE, October 2009

By Paul Brisby

Five-year-olds are prone to talk about it, as are winners of beauty contests. Pop stars sing about it and politicians often turn to it, especially as a justification for war. The idea of world peace has been a constant mantra to our times, but making it more than only words has so far eluded us. Whether between individuals, families, societies, countries or religions, peace has been hard to find.

From this November and over the following months, Cambodia, Thailand and the Philippines will host a series of talks by individuals who hope to bridge that divide and create a world where peace can jump from the placards and the negotiating table and become a reality. Their message, unlike that immature idealists and elated beauty contestants, is unlikely to be dismissed with an indulgent smile.

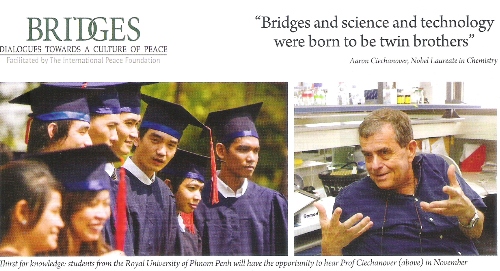

As one of the visiting speakers, Hong Kong actor and filmmaker Jackie Chan says: “To me peace means everyone living in harmony helping each other and caring for each other. It shouldn’t matter if people are black, white, yellow or red; we are all human beings and we need to have tolerance and of our differences.”

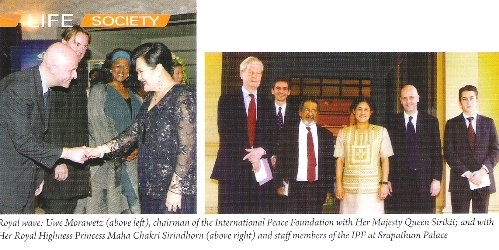

First launched in Thailand in 2003, Bridges — Dialogues Towards a Culture of Peace is a series of public lectures by Nobel laureates leading personalities in international politics, business and the arts, such as Jackie Chan, Oliver Stone, Vladimir Ashkenazy and Dr Jose Ramos-Horta.

The aim of Bridges is to foster communication and collaboration between representatives of science, politics, economics, culture, religion and all sections of southeast Asian society especially its youth. It also aims to establish long-term relationships with local leading to shared research programmes and other collaborations.

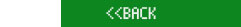

The initiative is the brainchild of Uwe Morawetz, chairman and co-founder of the Vienna-based International Peace Foundation (IPF), a non-profit, non-political and non-religious organization that with the help of 21 Nobel prize-winning patrons has organised more than 1,000 international education-based peace programmes in the past 20 years.

As well as providing a forum for dialogue, the IPF has started programmes of reconstruction in Kosovo, assistance for Aids victims and school-building in rural Thailand and relief for survivors of the Andaman tsunami.00

Morawetz is in no doubt of what the fundamental starting point is for a culture of peace: “To have peace you have to have dialogue. And before you can have dialogue, you need respect. Peace is a process that cannot be achieved instantly It needs time. Bridges was designed as an ongoing series of events in which Nobel laureates and international decision-makers build bridges with leaders in all sections of society and the general public.”

Bridges is the natural progression to the IPF-initiated Peace Summits that have been held in Europe since 1993, and have individuals involved the likes of the Dalai Lama, Henry Kissinger, Woody Allen, Elton John, Paul McCartney and Pink Floyd.

The first two series of the Bridges programme in the Asean region brought together 26 Nobel laureates as well as 13 other

keynote speakers and artists such as Dr Hans Blix, Rev Jesse Jackson, the late Dame Anita Roddick and Vanessa-Mae. This year’s event marks the expansion of the programme.

“When we started in Thailand we did not have any plans to expand to other countries in southeast Asia. However, because of the success of the first few events, the embassies acceptance of the other Asean countries began to approach us,” says Morawetz.

“After Thailand, the Philippines and Malaysia, Cambodia is the fourth Asean country to host Bridges and will be followed in the years ahead by all the Asean countries, with the exception of Myanmar.”

He was invited by King Sihamoni of Cambodia and Hun Sen, its prime minister, to bring Bridges to a country where a consensus for peace has made significant steps. It was an opportunity that delighted him. His enthusiasm is echoed by the first of those laureates to arrive, professor Aaron Ciechanover, who won the Nobel prize for Chemistry in 2004. “It is similar to my country Israel, 60 years ago, and is now making its first step as an independent democracy towards becoming a modern country and I am eager to see this transformation as it occurs and help as much as I can in bringing in my own experience as well as that of my country.”

The concept that the laureates come to learn as well as share knowledge is central to the philosophy of the Bridges programme. “Dialogue starts with listening ... we’re not just exporting something that we’ve done in another country. We’re also taking something back with us,” says Morawetz, who enjoyed Thailand so much that he has lived there for the past eight years.

Prof Ciechanover, who has already made a giant stride for the betterment of mankind through his discovery of the mechanics of protein degradation at a molecular level, will explain how science and technology can contribute to peace: “I think science and technology, if used for the benefit of human beings, are the best bridge on which one can walk to achieve peace and understanding among nations via development of modern agriculture, industry, health services, education, communication, transportation and welfare services. So, I think Bridges and science and technology were born to become twin brothers to bring peace to the world.”

He will be followed by five other Nobel laureates: Prof David Gross for physics, Prof Eric Maskin for economics, Prof Torsten Wiesel and Prof Francoise Barre-Sinoussi for medicine and Dr Jose Ramos-Horta for peace. The mix reflects Morawetz’s conviction that as a multi-faceted concept, peace can only be achieved by a multi-disciplinary approach.

“In our interdependent world, problems cannot be solved only by politicians and scientists or only religion and business, but by working together,’ he says. “Only if many ways cross and people walking these ways meet, can international understanding be achieved and problems commonly solved.”

When the Cambodian Bridges programme concludes in April2010, Morawetz will head to the African continent to prepare the ground for further Bridges events.

In 2012, Bridges programmes will start in South America, most probably in Brazil and Cuba, with the enthusiastic co-operation of the United Nations University for Peace in Costa Rica.

In his indefatigable pursuit of peace Morawetz seems to have recognised what Martin Luther King spoke of when he said: “One day we must come to see that peace is not merely a distant goal we seek, but that it is a means by which we arrive at that goal.”

“If I wasn’t at peace, I couldn’t work for peace,” says Morawetz. “I am happy I have seen many seeds reach fruition over the past decades, but I always yearn to see more. It’s this restlessness in peace that brings me joy and makes the work a success.”

The second speaker on the Bridges programme, Hong Kong actor, filmmaker and producer Jackie Chan, has worked tirelessly for humanitarian causes for years and is a Unicef and UNAids goodwill ambassador.

In 1988, he founded the Jackie Chan Charitable Foundation, which provides scholarships and medical aid to Hong Kong’s young people, and in 2005 he began the Dragon’s Heart Foundation, which provides assistance to children and the elderly in China’s more remote areas. Among other campaigns, he has promoted disaster relief efforts for the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami and the 2008 Sichuan earthquake.

A much-loved character among Cambodians, who know him as Chin Long, he is still remembered for his 2004 visit when he campaigned for Unicef against HIV-related stigma and for the banning of landmines.

Why do you think there is so much conflict around the world?

I think a lot of the conflict in the world starts with two people who disagree and then they convince others to take sides and things get all blown out of proportion. Really, conflict comes from intolerance and wanting everyone to see things the way we see them.

Do your extensive commitments to humanitarian causes ever impinge on your professional or personal life?

For many years I have had to balance the amount of time I spend on charity work with my film commitments. I think it has worked well, although I always wish that I had more time to do charity. However, I am a filmmaker and I think that if I hadn’t committed time to making films, no one would know me and then I wouldn’t be able to raise so much money for charity! I think it’s a good balance and I have never minded using my personal time (when I’m not making films) to do charity work.

What initially prompted you to set up the Jackie Chan Foundation in 1988?

A few things led up to my setting up the JCCF. During the filming of Armor of God in Yugoslavia, I suffered a fractured skull while performing a stunt. I was very lucky to be alive. It really changed my outlook on a lot of things. One result from the brush with death was that I began a charity foundation to try and give back to society and all those who had supported me for so long.

Another thing that comes to my mind happened many years ago. When I was a young and rising star, my manager arranged for me to visit to a children’s hospital at Christmas time. I remember that I showed up at the hospital and suddenly all these presents for the children appeared (my manager had bought and wrapped them).

When the kids opened the presents their eyes lit up and they kept thanking me and telling me how much they loved me. I felt so awful! I felt like such a fake because I didn’t know anything about the presents and the kids thought I’d given them personally.

From that day on I vowed never to repeat that kind of behavior. After that I always pick out the presents myself and make sure that I take care of these less fortunate, especially children.

When you were young did you ever think you would achieve such recognition in the film world, as a humanitarian ambassador and now as an advocate for world peace?

When I was a young boy in the China Drama Academy (Peking Opera School), I didn’t think much about fame and fortune. It was a struggle just to get through each day; to find enough to eat, to avoid being beaten by my masters, just to survive. That sounds dramatic, but it’s all true!

As I got older and began working in films as a stunt man, my dreams began to focus on being famous and making lots of money. When I started to become famous, I was quite arrogant and thought only about myself and buying lots of watches and cars. I didn’t think much about charity. Later, after the accident in Yugoslavia, I changed my thinking and realized that I should be thinking of others, not just about me. It was natural progression to become a humanitarian and I’m very proud of the work I’ve done for charity. I am happy that my fame allows me to bring attention to the problems in the world.

How do you find the energy to fulfill your multiple roles in life?

I am naturally a very energetic person, so I don’t have a problem finding the energy to do all the things I do. I rest whenever there is an opportunity and then when I’m needed, I wake up and am ready to go.

Do you think that the martial arts tradition exemplifies the idea that If you want peace you must be prepared for war?

Martial arts teaches discipline and self-control. It’s also a very good form of exercise, and exercise is good for the body and for the mind. I don’t think about martial arts in terms of preparing for war. For me it’s just a way of life.

During your last visit to Cambodia, what made the biggest impression on you?

Of course I was shocked by the numbers of men, women and children who had been maimed by landmines buried in the fields near their homes.

But I was most impressed by how warm and friendly the people were, and that they could have such a positive attitude despite their terrible injuries.

Is there any chance of you making a full length feature in Cambodia?

When I visited Cambodia five years ago with Unicef, I thought that there must be a thousand stories there that would make a good movie. Right now my schedule is filled for the next few years, but someday I’d like to make a movie in Cambodia.

What advice would you have for the youth of Cambodia as they face the world?

I know that young people don’t like to have old people give them advice, but if I had to tell them something, I’d tell them to respect their parents, avoid trouble with the law and try to think about others.

It’s not important to have all the latest gadgets and expensive clothes; it’s important to be a good person and take care of each other. I would tell them to exercise and eat right and that if they do this they will feel content. And when you feel good, it’s easy to deal with all the problems in your life.

|

|

|